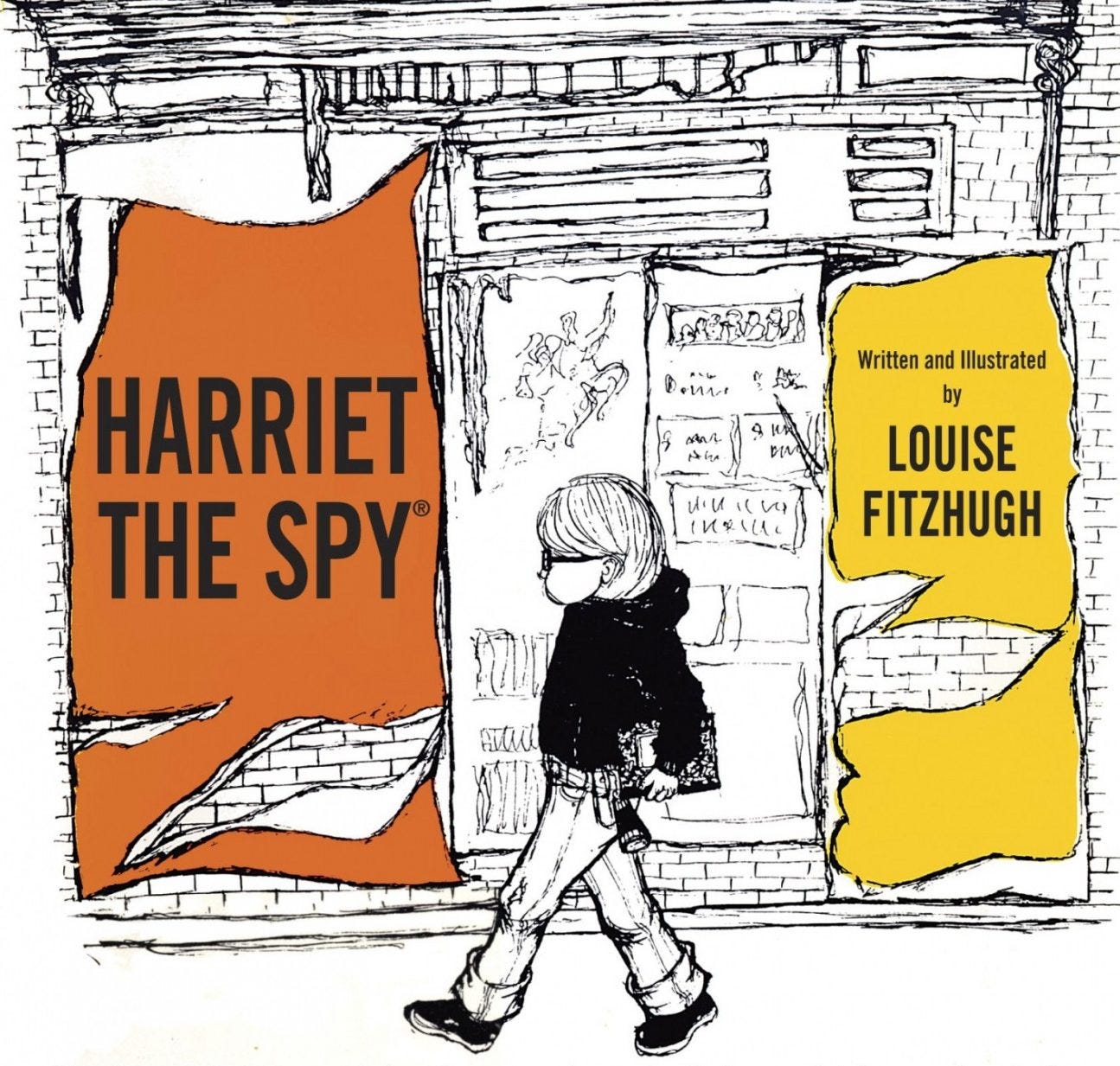

I got a new tattoo this summer. I had been planning it for at least a year. I knew just what I wanted too: a sketch of Harriet M. Welsch, based on the illustrations in the 1964 edition of the children’s novel, Harriet the Spy, written and illustrated by Louise Fitzhugh.

When I told my friend, Sam, about my Harriet the Spy tattoo plan she said, “I hate to break it to you, but that’s hardly an original idea.” She pulled out her phone and began a Google image search, and sure enough, dozens of different tattoos, exactly like the one I wanted.

So what? I didn’t care. Sam has lots of tattoos, lots of very cool tattoos, but one, a reproduction of Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam, which if Wikipedia is to believed, is the most reproduced religious painting of all time, is probably even more unoriginal than Harriet. So what? Sam didn’t care.

Originality is not a make-or-break criteria for a tattoo for me. Maybe it is for you. It is okay to latch on to someone else’s story, which is what I’ve done with Harriet since I first discovered her at age 10. Sam has her personal reasons for inking God’s hand reaching out to mankind on her skin. Stories become classics, retold over and over because they speak to our human condition.

Harriet taught me to be curious about everything. While her spy route (think a neighborhood paper route, but with no deliveries and interludes of Harriet stopping to write down juicy observations about what she sees). Her spy route had a delicious deviancy about it: staring at others and writing acerbic commentary about them. Her experience encapsulates the ambitions and difficulties of writing the truth about other people. There’s a twist of cruelty in the way Harriet writes about her friends and classmates. Truth hurts, Harriet realizes (especially when she’s varnished it with her own self-serving judgments and prejudices).

When her friends accidentally find her spy notebook, and they read Harriet’s unflattering portraits, they hate her for it. Here is one of the hardest and ongoing problems of a memoirist: you have to write about real people in your life, and even if you’d try to be fair (but also honest), you never know how they’re going to react. Emotionally, that was the hardest part of publishing a book (luckily, my mother, mother-in-law, and spouse have been fine with their depictions in my memoir). And here’s a spoiler alert: Harriet eventually makes amends and learns to become more thoughtful and nuanced in what she writes about other people, to get at a more honest truth, which makes her a better writer. She learns to see perspectives other than her own.

Harriet is my writer archetype, so a month after What Will Outlast Me? was published, I had her permanently inked, sitting cross-legged, scribbling in her notebook, on my left bicep.

“I want to know everything and write it all down,” Harriet declares in the 1996 Nickelodeon film adaption. As I’ve thought about my writerly apologia, I realize Harriet’s intrinsic motivation is what inspires me, too. (I should note: middle age has bestowed a humility that recognizes—even as it admires—the reckless hubris of believing I could know everything!) However, when I think and write about something it’s because I have an insatiable urge to know everything I can about it. (What Will Outlast Me? contains 18 pages of research endnotes). The core reason I write is because of the pleasure that comes from deep knowing, understanding, and noticing my life and the lives of those around me in the world we all share. Wow. It’s awe-inspiring.