Today is Maundy Thursday, a day celebrated in Christian liturgical tradition with foot washing during the Holy Week leading up to Easter. "Maundy" comes from the Latin word mandatum, or commandment, reflecting Jesus' words "I give you a new commandment."

At the Last Supper, Jesus demonstrated the powerful practice of humility by washing his disciples’ feet. Jesus’s most intimate followers were taken aback by this unexpected gesture of meekness, and yet humility (and surprising spiritual teachers) are themes that echo across religions. Jesus reminds me a lot of Buddha.

“Humility is one of the ten sacred qualities attributed to Avalokite Bodhisattva, or Buddha of Compassion,” writes Chen Yu-Hsi, and “within that context, it appears to be a natural by-product of supreme spiritual attainments that transcends the ego, just as are the four noble states of mind -- love, compassion, sympathetic joy and equanimity.”

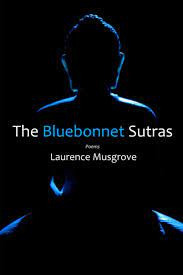

Today I’ve interviewed poet, professor, and Buddhist, Laurence Musgrove, author of The Bluebonnet Sutras (Lamar Press, 2019), which is a beautiful, strikingly humble, often surprising collection of poems written in conversation with Buddha.

Let’s start with the title: The Bluebonnet Sutras. In Sanskrit, sutra means “thread” or “string,” but in Buddhism, it’s a form of scripture. Do your poetry sutras fit these definitions?

I named my poems “sutras” because they include teachings. These teachings come in response to questions that I direct to an imagined Buddha who is portrayed in various ways, sometimes as the historical venerated teacher but more often as a friend.

These poems began as a way for me to process my studies in Buddhism, and they helped me clarify and make memorable what I was learning. The poems also helped me apply what I was learning to my everyday experience and current events by asking myself, “What perspective might the Buddhist wisdom tradition offer?”

It’s still a question I use frequently to ignite a poem or new sutra. A recent poem “Black Bean Sutra” will be published in an upcoming issue of Pensive: A Global Journal of Spirituality and the Arts, and it derived from a concern I was having about how we are continuously bombarded with advice on how easy it is to change our lives.

I used the analogy of slow-cooking beans to represent how we are all steeped in our family inheritances and cultural influences. The Buddha in this poem acknowledges the difficulty of change, especially when we fail to accept all that has already shaped us so deeply, so persistently, and so unconsciously.

In last week’s post, I wrote about the value of having imaginary conversations, and each Bluebonnet sutra is an imaginary conversation with Buddha. What inspired you to include Buddha as a character in these poems?

I was inspired to use the Buddha in these sutras after reading Billy Collins’ poem “Shoveling the Snow with Buddha.” In his poem, the narrator and his companion the Buddha are clearing a driveway, and the narrator is excitedly talking too much as the Buddha quietly shovels away. Then, after a long silence, the

Buddha turns to him:

After this, he asks,

can we go inside and play cards?

Certainly, I reply, and I will heat some milk

and bring cups of hot chocolate to the table

while you shuffle the deck

and our boots stand dripping by the door.

Aaah, says the Buddha, lifting his eyes

and leaning for a moment on his shovel

before he drives the thin blade again

deep into the glittering white snow.

After reading this poem, I felt I had permission to include this quiet, wise, spiritual presence or personification of my Buddhist studies in my own work, too. It’s very comforting to me that I can call upon him at any time and be certain he will respond. I’m sure others feel the same way about their own spiritual companions.

One thing I love about these poems is how surprising Buddha is on the page: he does dishes, stands in line at HEB, and emails. Did anything surprise you during the creation of these poems?

I’m happy that you found moments in these poems both satisfying and surprising. I think poetry should always offer us a surprise of some sort, a turn of phrase or a combination of images, even a connection to another we thought impossible.

One of my favorite authors, Stephen Dobyns, writes in Best Words, Best Order: Essays on Poetry that narrative creates suspense and poetry creates surprise. I like that.

I was surprised most that the conversation format was so productive for me. By that I mean, I didn’t realize that these sutras would become a subgenre path for me that I would continue to explore as I progressed through my Buddhist studies. Ultimately, they are my translations of the teachings that were most powerful for me. They are more powerful I think because I set them in contemporary settings and situations, like in my house or on a dog walk or while preparing a meal.

A reoccurring theme I explore in Spirit is how spirituality informs creativity. How have your spiritual practices nourished your creative practice, and vice versa?

My creativity is my spiritual practice because in my poems I express my beliefs about what is right and wrong, beautiful and ugly, and true and false about myself, others, and the world. They are all teachings; that is, they reflect what I believe and would want others to consider and experience as well. In the case of the sutra poems, they are more explicitly didactive and narrative than my other poems, which are no less spiritual I suppose.

Still, “spirit” and “spirituality” are not terms I naturally default to. I know they work for others, but not me. Maybe I’ll be able to embrace them in the future, but for now, they carry baggage that I haven’t set down.

“Interbeing” is a more productive term for me: a Buddhist concept originated by Thich Nhat Hanh. I admit that it is a difficult idea to grasp because we are so used to thinking of ourselves as unique and individual bodies, minds, and hearts, separate and distinct beings impenetrable by others, often even a mystery to ourselves. However, “interbeing” maintains that we have more in common with others and the world than differences. We share the same material and energy. And our purpose in life is to prepare for our eventual return to the common storehouse of material and energy. All of us are on borrowed time. And how are we to prepare for our return? We should live in a way that best shares and best preserves the material and energy for other beings to manifest. And that’s what literature is for: to remind us how to share and preserve, rather than to horde and destroy.

One way you share and preserve is through the work you do with the Texas Poetry Assignment. Can you tell us a little about what the Texas Poetry Assignment does?

Texas Poetry Assignment is a non-profit arts organization inspiring community through hunger relief and poetry in Texas. We offer a list of poetry resources, extend calls for submission, publish exemplary poems, host monthly online readings, and support anti-hunger efforts in Texas via Feeding Texas.

Our most recent assignment is “Dialogue Poems” which invites poets to compose poems that contain a dialogue or conversation or interview between two voices, personified, fictional or real.

Our next reading event related to this assignment will be on Sunday, April 24 at 7 pm CST, and your readers are certainly invited to submit to Texas Poetry Assignment and join our reading events.

I’d also be happy to continue this conversation with you and your readers any time. Peace to us and all.

Thanks Laurence!

Thank you, Sarah!

One thing that occurred to me, while reading this marvelous book, is the first lines from Hakuin Ekkaku's "Hymn in the Prize of Zazen":

"From the beginning all beings are Buddhas

like water and ice:

without water, there is no ice

outside us, there are no Buddhas"

Thank you for these poems, Laurence

Thank you for the interview, Sarah!

Stefan Sencerz