I’m almost asleep when my cat, who’s curled against my feet, bolts upright. Then I hear the padding footsteps of my 4-year-old son, Stanley. The cat leaps off the foot of the bed to avoid him. He materializes, ghostlike, at the side of my bed.

“I’m scared,” he says. I let him climb under the covers with me. His damp, blonde hair curls at the nape of his neck. When he hugs me, I feel his pounding heart and hear his shallow, quick breaths. It’s another nightmare. After weeks of nightmares, I feel helpless.

“You know dreams aren’t real, so nothing in a dream can hurt you,” I say.

“But dreams have real things in them!”

I’m stymied because as a life-long nightmare sufferer, I know he’s right.

I can either let him sleep in the Big Bed, spending the rest of the night getting kicked in the ribs, or I can go back to his room and stay with him until he falls asleep again, which depending on his terror level, can take over an hour, with no guarantee he won’t be back again around 3 am.

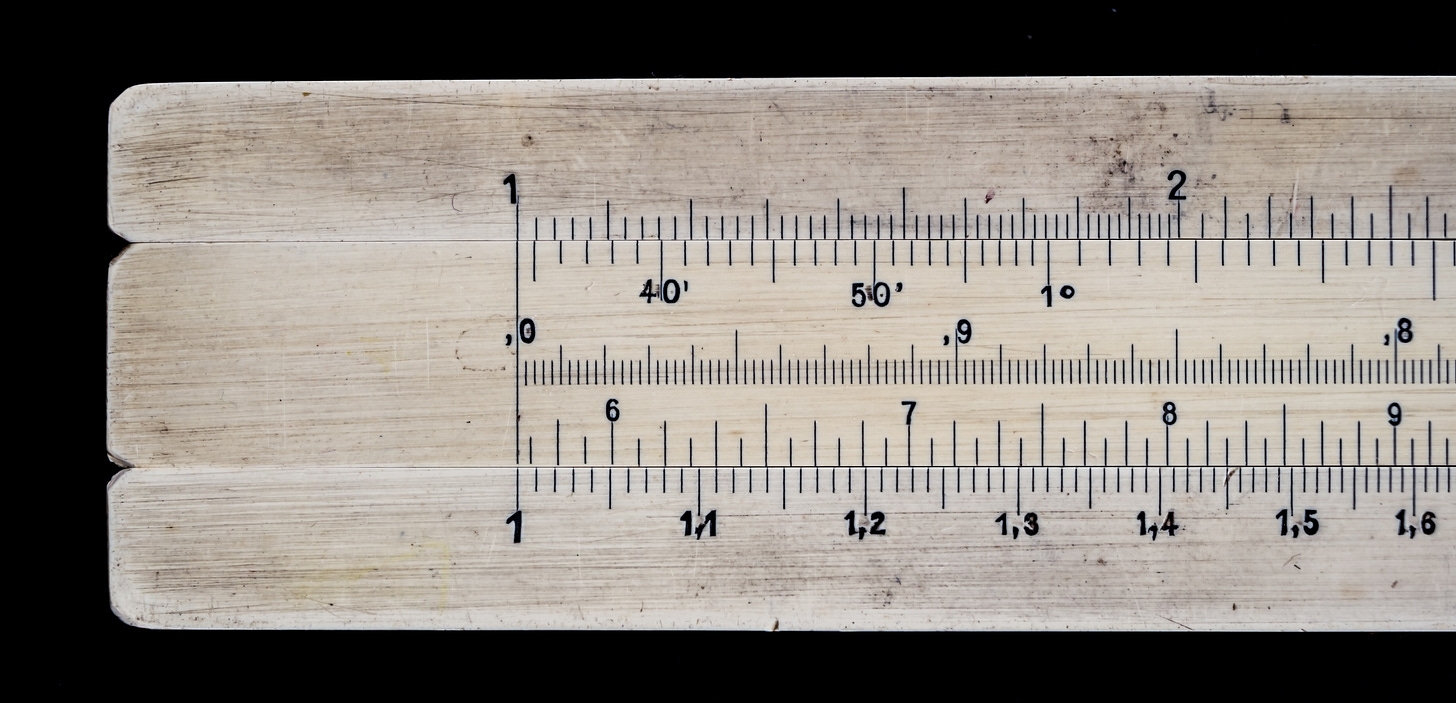

Here’s what I won’t do: what my father did to me when I was Stanley’s age. I won’t stand guard outside the door with a yardstick. I won’t thwack it violently on the floor. I won’t hit his ankles and feet when he tries to flee his room from a night terror.

The Yardstick Incident has been retold in my family for as long as I can remember. “Your dad got drunk. He was always drunk,” Mom said, “and one night he was bound and determined you were going to stay in your room all night. Every time he finished a beer, he threw the empty can down the stairs, where I waited at the kitchen table, too afraid to intervene.”

The Yardstick Incident appears in “Driving the Section Line,” the first essay of my forthcoming collection, What Will Outlast Me? You can listen to a Podcast of it here:

When I first drafted “Driving the Section Line,” a part of me thought I shouldn’t tell it. It was too raw. It villainized my dad. But because it happened to me, it’s also my story to tell.

Ann Lamott writes in Bird by Bird: “You own everything that happened to you. Tell your stories. If people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should have behaved better.”

I wrote about the Yardstick Incident because I wanted to convey the difficulty of growing up with an alcoholic father, to show how his weaknesses and failures have followed me, but to also get at the complexity of traumatic memories, and how they’ve resulted in lifelong shame.

“I didn’t hit you,” Dad told me years later as if to justify it all. “I sure as hell made a lot of noise though. Scared the living shit out of you. Now if you have mental problems, you can blame it on me. But I think you turned out fine. It worked too. You always slept in your own bed after that.”

In his version, he emerges the hero, successfully sleep training his preschool-age daughter. Now that I’m a mother, the Yardstick Incident has shifted meaning again. I am even more horrified at the violence now that I see firsthand how terror over nightmares manifest in my own preschooler’s body. I understand the how frustrating it is to lose sleep, to not be able to solve the child’s nightmare problem, but I also feel a sad sort of pity. Fueled by alcohol, he had no other tools in his parenting arsenal, and he either didn’t know or care to do better. But he also didn’t have a support system like I do.

My church hosts Compline prayer service every night at 9 pm via Facebook Live. One night Stanley comes into my bedroom after a nightmare, and he finds me with my phone and my Book of Common Prayer, praying. He knows Ms. Alice, who’s leading Compline, and he watches with me, growing calmer by the collect . When Alice asks for prayers of intercession, I type in the comments: “Prayers that Stanley’s bad dreams will go away.” I tell him what I’m doing, and when Alice prays for him by name, over the digital airwaves, he gasps in awe.

I am relieved to share our struggle in this simple way, to surrender the notion that I can control and fix it. Perhaps a grating sense of powerlessness led my dad to his violence.

Stanley’s nightmares don’t go away at first, but the intercessory prayers continue, and our spiritual community heaps love on us. One friend, Lou Ella, gives Stanley a tiny box of Guatemalan worry dolls and a note. I am touched by the kindness. The real power of collective prayer rests in its ability to cue us in to one another’s needs and to act. It’s easy to forget I’m a tool God uses to answer prayers too.

I think I tell the Yardstick Incident as a cautionary tale, too. I understand how easy it is to slip into cruelty. I shiver when I think how easily I could be just like my father, especially if I was still drinking. I also wish that he would have had an outpouring of prayers like Stanley and I have had.

A week and a half later, the nightmares dissipated, another painful childhood phase that we’ve muddled through for now, and in the mean time I keep praying my bedtime prayers:

Be present, O merciful God, and protect us through the hours

of this night, so that we who are wearied by the changes and

chances of this life may rest in your eternal changelessness.

This is such a heartbreakingly beautiful piece of art. Thank you for sharing this with us.

Wonderful post. I’ve seen the power of the Book of Common Prayer in our lives. Intercession does tune us into others’ needs. That’s quite an answer to prayer for your son’s night terrors to go away.