I was cooking dinner when I heard Stanley scream, “Oh, my God! I have such a loose tooth!” I stopped chopping carrots and went to the living room to see what was going on.

He’d been playing a rousing game he calls Rollercoaster, which involves strapping an extra heavy exercise resistance band around the crossbar of the built-in shelves between our living room and dining room. Once the band is secured, he grabs on, sits on a throw pillow stolen from the couch, and with a combination crab-walk and butt-scoot that requires his whole body weight and arm and leg strength combined, he inches his way backwards on the hardwood floor. He gains tension. The resistance band stretches to its full capacity. Then, Stanley lifts his feet in air, the band snaps him forward like a slingshot.

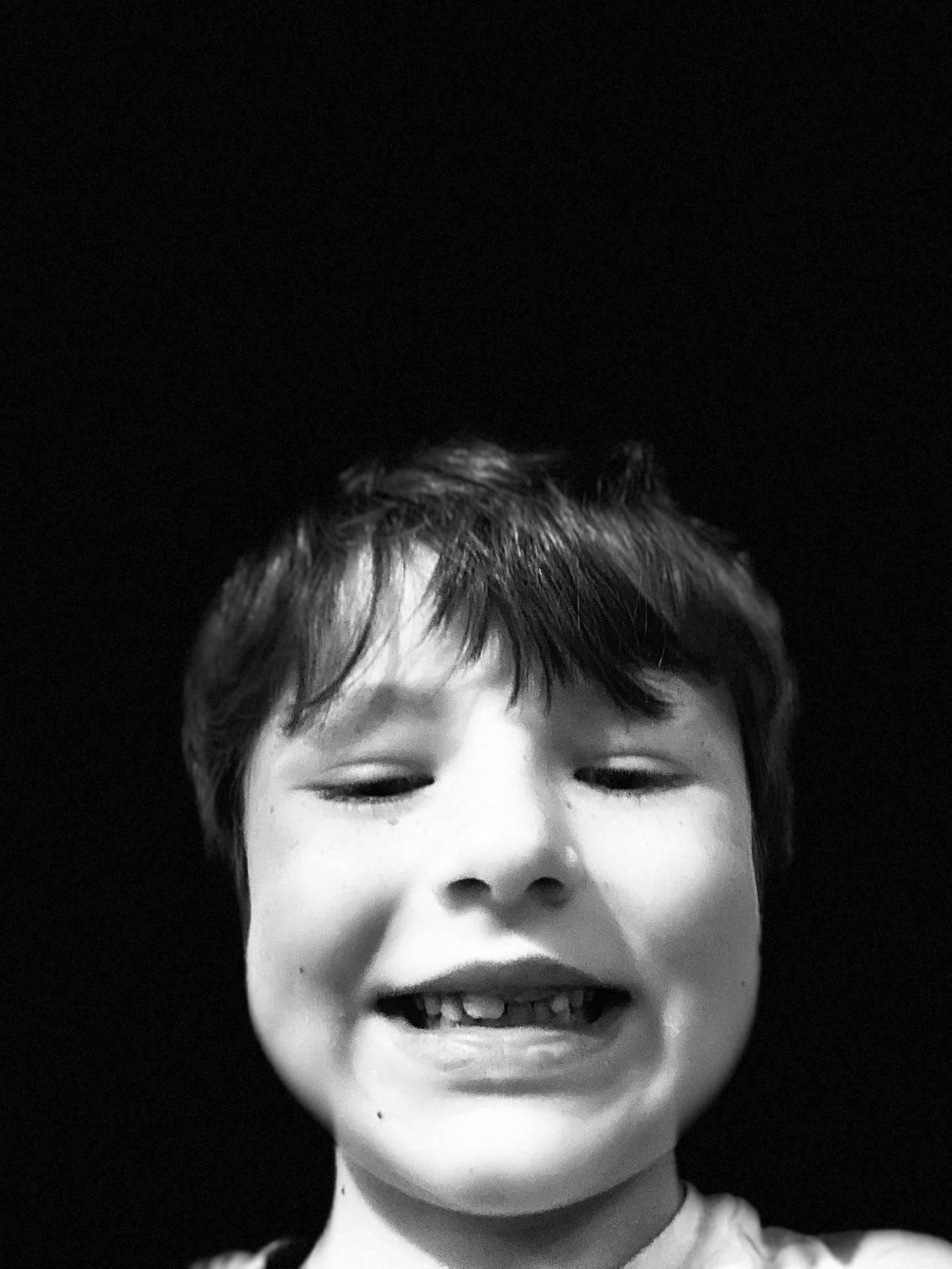

This time, when the elastic band shot him forward, the force jabbed his knee into his mouth. At six, Stanley’s mouth is jack-o-lantern smile of missing teeth, a mismatched mix of baby and permanent teeth. The blow to his mouth didn’t actually dislodge a tooth or cause any bleeding.

Once I saw he was okay, I thought maybe I should reprimand him for taking the Lord’s name in vain. I’d never heard him use the expression before, which in retrospect was more startling than the fear that he’d knocked a tooth out of his head. He’s been losing teeth for months now.

Rollercoaster is a game he invented himself, the type of open-ended imaginative and kinetic play that I’ve read is best for kids. It seems safe enough. The poor throw pillow Stanley uses as the rollercoaster takes the brunt of wear and tear—and it was a cheap impulse buy at Walmart. I don’t care if he ruins it.

My leniency also comes from remembering that I played a game like this when I was his age. Bucking Broncos consisted of riding couch cushions down the stairs like it was a rodeo. The more raucous tumbling, the better. I get it. This innate craving kids have to push their bodies to their limits. To be wildly kinetic. Daily.

In Secrets of Childhood, Maria Montessori writes, “The child does not follow the law of the least effort, but a law directly contrary. He uses an immense amount of energy over an unsubstantial end, and he spends it not only driving energy, but intensive energy in the exact execution of every detail.”1

The key feature of maximum effort is that the greater amount of effort involved in the work, the greater the sense of satisfaction.

Maximum effort is the young-child’s version of what Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi famously named flow, a state of being immersed in a task so wholeheartedly without distraction that the world’s worries dissolve and one’s sense of clock-time disappears.

Csikszentmihalyi explains, “The best moments in our lives are not the passive, receptive, relaxing times . . . The best moments usually occur if a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile.” 2

Flow states are a wellspring of happiness.

Flow can be hard to come by though. Distractions are everywhere. I carry the ultimate distraction machine with me wherever I go, and it will ding all day long with every text message, email, or social media notification I receive if I let it.

In a conversation with my writing students recently, the majority said that they couldn’t sit down to write if they didn’t have either music on or were playing a movie or tv show on another screen nearby. I was horrified. How can you even think, let alone enter a flow state with that much noise and stimulation? “Oh, it helps me focus,” one student shrugged. “And I take frequent phone breaks, too, just to go on Instagram.”

“The habits of multitasking are so ingrained that we don’t recognize when we are distracted; it has become a normal state of being…We are so accustomed to being distracted that we no longer know what it means to be focused, to dwell in our thoughts, to think deeply about matters that don’t lend themselves to a snarky tweet,” explains Ann Jurecic in The Habits of a Creative Mind.

When exactly, did I go from chasing down maximum effort, to being like my students: having 15 tabs open on my browser when I try to write, a Spotify playlist blaring in the background, and my email inbox and text message notifications chiming at me intermittently, but constantly. How can I notice anything in this din?

I’m not giving myself up to the sheer unmitigated pleasure of being engrossed in a maximum effort endeavor either. There are not enough Rollercoaster games in my life that I’m throwing my whole self into. I want more Bucking Bronco rounds in which I’m hurling down the metaphorical stairs with complete concentration of the moment.

Since my first book, What Will Outlast Me? was published in June, I’ve been creatively adrift, trying to find my next book project—knowing that when I land on it—I will need to string together hours, days, weeks, months, years of maximum-effort sessions to complete it. It will be exhausting. It will also make me happy. The process of it, in and of itself, is where the pleasure lies. Of course, I want a second book to go into the world, to be published and praised, but there’s no guarantee that it will happen. It make come to an unsubstantial end.

Process not product, I remind myself, which brings me to Stanley’s exclamation. “Oh, my God!” After I thought about it, I realized he’s not taking God’s name in vain. He’s really calling out to the Creator in wonder and joy (which so often bubbles up in flow states.) It’s why I return to contemplative practices too: mediation, yoga, labyrinth walking. They require concentration (maximum effort). If I can immerse myself in my chosen work, work that is difficult and worthwhile, God will show up.

May we all find those moments where we can’t help but exclaim, Oh, my God! which is to say, Oh, my God, what a strange and beautiful world! or Oh, my God, what a time to be alive! or Oh, my God, how fearfully and wonderfully we’re made…when our baby teeth drop out of our mouths…and when our permanent teeth grow in, may we not forget our childhood love for maximum effort.